For much of the past decade, American foreign policy has felt confused, cautious and often reactive. Allies were unsure where the US stood. Adversaries tested limits. Too often, decisions seemed driven by short-term political pressures rather than a clear long-term strategy, creating a vacuum in global leadership. In that space, rivals like China, Russia and Iran moved more aggressively to expand their influence, while partners in Europe and the Middle East began questioning whether Washington was still willing and able to lead.

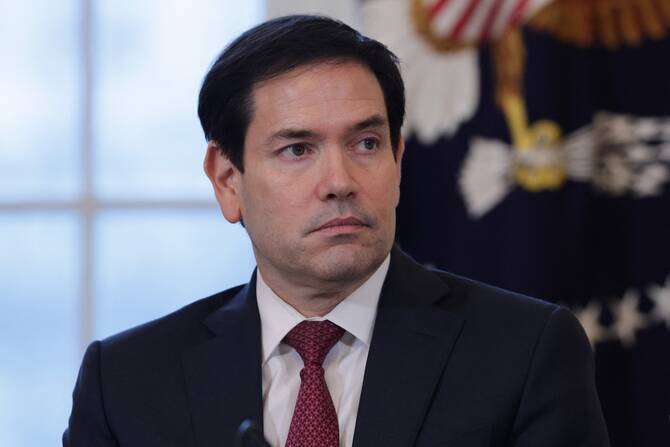

In this context, a strong argument can be made that Marco Rubio is emerging as one of the most effective secretaries of state in modern American history. Not because of dramatic gestures or media attention but because he has brought back something essential to US diplomacy: strategic seriousness.

Rubio understands a basic truth that many policymakers lost sight of: foreign policy is not about being liked. It is about power, security and responsibility. The purpose of American diplomacy is not to seek applause but to defend national interests, stand with allies and stop threats before they turn into conflicts.

The world Rubio faces is more dangerous than at any time since the end of the Cold War. China is expanding its economic and military reach across Asia, Africa and Latin America. Russia continues to challenge the global order through aggression and coercion. Iran fuels instability across the Middle East through proxy militias and ideological warfare. At the same time, international institutions are weaker, global trust is lower and conflicts spread faster than before.

It is about honesty. Rubio understands that diplomacy built on false assumptions leads to failed policies

Dalia Al-Aqidi

The Florida politician, who has spent more than half his life in public service, does not rely on wishful thinking to confront global challenges. His approach is grounded in realism: that power cannot be ignored, threats must be faced directly and lasting peace is built through strength and clear-eyed judgment, not comforting illusions.

One of Rubio’s most notable qualities is clarity. He speaks about authoritarian regimes without hiding behind vague diplomatic language. He calls out Beijing’s strategic ambitions, not as competition but as a long-term challenge to democratic systems. He treats Tehran not as a misunderstood actor but as a revolutionary regime that uses violence, ideology and intimidation to expand its influence. He recognizes that Moscow is not simply reacting to Western policy but actively seeking to weaken the rules-based international order. This clarity is not about confrontation for its own sake. It is about honesty. Rubio understands that diplomacy built on false assumptions leads to failed policies. You cannot negotiate effectively if you refuse to admit what you are negotiating against.

At the same time, the American official has shown that strength does not mean recklessness. He does not seek endless wars or military escalation. Instead, he focuses on prevention: making clear that aggression will be costly, while keeping diplomatic channels open for serious negotiation. This balance, firmness without chaos, is one of the most difficult skills in foreign policy and one of the most valuable.

Rubio also restores moral clarity to American diplomacy. For years, the US hesitated to speak firmly about its values. Human rights were applied unevenly and democracy often sounded more like a talking point than a real commitment. Rubio brings the focus back to a simple belief: that freedom, the rule of law and human dignity are not special privileges for the West but fundamental rights people everywhere want and deserve. This matters deeply for international audiences. When the US speaks with moral uncertainty, authoritarian regimes fill the vacuum with their own narratives. When America is clear about what it stands for, it gives courage to reformers, dissidents, journalists and civil society actors across the world.

Rubio’s support for democratic allies is not symbolic. He understands that alliances are not acts of charity; they are strategic assets. He treats partners in Europe, Asia and the Middle East as force multipliers that strengthen global stability. Whether in supporting NATO, strengthening ties with Indo-Pacific democracies or reinforcing partnerships in the Middle East, he has made it clear that the US does not lead alone, but it must still lead.

To understand Rubio’s place in history, it helps to compare him with some of the most respected Republican secretaries of state.

George Shultz, who served under Ronald Reagan, believed that effective diplomacy must be built on strength. In the Cold War, he pushed back firmly against the Soviet Union while still maintaining open lines of communication. His calm and consistent leadership helped shift the world from constant tension toward meaningful arms control and stability.

He treats partners in Europe, Asia and the Middle East as force multipliers that strengthen global stability

Dalia Al-Aqidi

James Baker, under President George H.W. Bush, managed the end of the Cold War with rare skill. He built international coalitions, maintained alliances and navigated the collapse of the Soviet system without triumphalism or chaos. His diplomacy was pragmatic, disciplined and effective.

Henry Kissinger, though controversial, changed global diplomacy by accepting how power really works. He believed that ideals mean little without a clear strategy and that American interests must stay at the center of foreign policy choices.

What Rubio shares with these figures is not their personality or era but their seriousness. Like them, he treats foreign policy as a discipline, not a performance.

However, Rubio’s main weakness, according to critics, is that his strong moral view of global politics can limit the flexibility of diplomacy. In many parts of the world, especially in the Middle East, Africa and parts of Asia, Washington must often work with imperfect partners to prevent larger crises. Rubio’s preference for firm language, sanctions and public pressure, while powerful tools, can at times narrow diplomatic options and harden positions. Critics argue that an overreliance on pressure risks pushing hostile regimes closer to rivals like China and Russia and closing channels that could be useful for de-escalation.

In simple terms, Rubio is excellent at drawing clear lines but real diplomacy often takes place in the gray areas, where patience, compromise and discreet engagement are also necessary.

The international community does not need a perfect America but it does need a clear and steady one. When US policy is uncertain, global instability grows. When it is grounded, consistent and guided by principles, nations can plan ahead, work together and manage conflicts with greater confidence.

In a world marked by rising authoritarianism, weak institutions and growing insecurity, these are not luxuries. They are necessities.

BY: Writer Dalia Al-Aqidi is executive director at the American Center for Counter Extremism.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect The Times Union‘ point of view