- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev scientists find middle-aged mice who lost weight in peer-reviewed study were prone to inflammation linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s

While weight loss in middle age could help the waistline, it may also hurt the brain, researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev have warned.

The scientists found that after diet-induced obesity in middle-aged mice, weight loss lowered blood glucose, which is a positive benefit. However, it also caused aggravated inflammation in the hypothalamus, a region in the brain that regulates appetite, energy balance and many other vital functions. Similar inflammation is known to be linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The new study, led by MD-PhD student Alon Zemer and Dr. Alexandra Tsitrina at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, under the supervision of Faculty of Health Sciences Prof. Assaf Rudich of the Obesity Research Lab and Prof. Alon Monsonego of the Neuroimmunology Lab, recently appeared in the peer-reviewed journal, Gero-Science.

The unexpected findings raise new questions about how weight loss in midlife may impact brain health.

“Weight loss remains essential for restoring metabolic health in obesity,” Zemer told The Times of Israel in a teleconference call with Rudich. “But we need to understand the impact of weight loss on the mid-age brain and ensure brain health is not compromised.”

People in their middle age “are increasingly likely to try and lose weight by dieting, with anti-obesity medications, or surgery,” Rudich said. “The findings show that we need to make sure we are not igniting an unwanted inflammatory response in the brain during the active phase of losing weight.”

Studies about weight gain, but not weight loss

It is estimated that 64 percent of Israelis are overweight or obese according to World Health Organization standards.

However, Rudich said that he and Zemer found that most basic research using mouse models largely ignored the investigation of what happens to the body after weight loss.

“Most of the line of research is about young mice gaining weight,” he said. “We wanted to look at processes occurring during weight loss instead of weight gain, and specifically in older individuals.”

In the study, the researchers monitored the weight gain and loss of young mice, similar to 20-year-old humans, as well as middle-aged mice, comparable to individuals aged approximately 40 years or older. (One mouse year is equivalent to 40 human years.)

“We gave them a high-fat diet and they were gaining weight really nicely,” said Zemer. “They almost doubled their weight following eight weeks of this diet. We just let them eat as much as they wanted. Following these eight weeks, we reversed it. Half of the high-fat group went back to a controlled diet, and we let them lose weight, kind of naturally.”

The scientists said that both the younger and older mice lost weight quickly. Their bodies became healthier, with blood sugar levels returning to normal in both groups. Since high blood sugar can lead to diabetes, lowering it benefits the body.

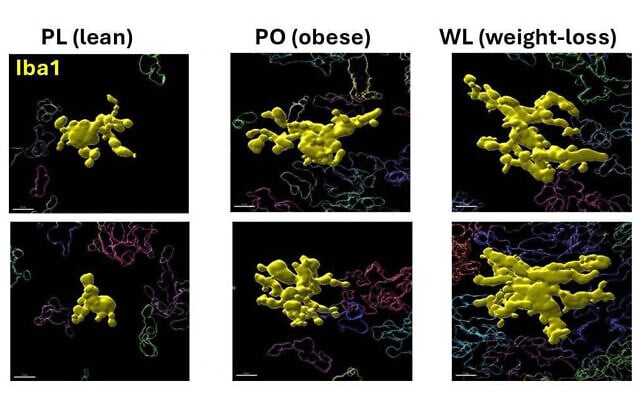

The older mice lost almost 60% of the extra weight they had gained. However, when the scientists looked closely at their brains, they found neuroinflammation of the microglia, the brain’s immune cells. The microglia regulate brain development and neuronal networks.

“The middle-aged brain appears to be sensitive to this weight loss, and during the period of losing weight, responds with increased neuroinflammation beyond that already triggered by obesity,” Zemer said. “And this is something that occurs in mid-age but is not apparent in young adult mice.”

Studying the changes on the molecular and structural levels

Tsitrina said that high-advanced microscopy and image analysis with advanced computational analysis enabled the detection of sensitive changes in the microglia.

She explained that the study showed the body’s adaptive response to weight loss through two complementary dimensions: on a molecular level, by examining signals inside the cells, and on a structural level, by examining the shape and activity of the brain cells. These findings have “potential health ramifications,” she said.

The researchers understand that people want to “relieve the risks associated with obesity,” said Rudich. “But we need to test it closely because sometimes we come up with surprising results that make us think in new directions. So, research not only provides answers, but it also brings up new questions.”

“The study demonstrated that not all weight loss is alike,” said Dr. Amir Tirosh of Sheba Medical Center’s Endocrinology and Diabetes Research Center, who is not connected to the study.

In a written reply to The Times of Israel, Tirosh said that since the study uses a mouse model and needs to be validated in humans, “we will need more studies to understand the long-term effects of this remaining brain inflammation.”

Zemer said that the research team is now embarking on a new study to look at different areas of the hypothalamus and to try to gain an even deeper understanding of what is happening with these cells, and what processes can or cannot be reversed.

“We want to understand what happens when people lose weight and then, six months later, gain back every single pound they lost during this time,” Zemer said. “Do we get any beneficial effect from this weight loss? Or, is it somehow preferable to be weight-stable? Do we gain health benefits by being lean or less obese, even if it is temporary, for several years only?”

“Weight loss requires further investigation,” said Rudich. “We might need to take action to try and protect the middle-aged brain when attempting to treat obesity.”

BY: Diana Bletter